While many of us have not even heard of adlai, this tall-grain bearing tropical plant from Poaceae (grass family), the same family to which wheat, corn, and rice belong, has been abundantly growing in the country and is being cultivated since ancient times as staple food. In Midsalip, Zamboanga del Sur, adlai is extensively cultivated synanymous to rice.

“The Subanen people have been growing adlai for as long as I could remember. When I was still a child, I saw how they plant this crop as source of food,” said Terso Balides, a Subanen farmer in Midsalip.

The Subanen people are the aborigines of the Island of Mindanao and considered as the first inhabitants of Pagadian City in Zamboanga del Sur. Their ancestors have been growing adlai as staple food in the highlands, the way the lowland people eat rice. They commonly grow it in kaingin areas, freely branching upright, thriving robustly even in marginalized areas.

Even though adlai is being cultivated since ancient times, a lot of Filipinos are still unfamiliar with the crop. It was only very recently, that adlai is gaining familiarity among Filipino rice-eaters through the efforts of the Department of Agriculture (DA) under the leadership of Secretary Proceso J. Alcala wherein adlai is being widely promoted as one of the staple crops that could possibly bring Filipinos to food self-sufficiency.

In Septemeber 2010, the Bureau of Agricultural Research (BAR), as the lead research and development (R&D) agency of DA, was tasked to look into the potential of adlai as an alternative crop for rice and corn. BAR met with two non-government organizations (NGOs), Earthkeepers and MASIPAG to explore the potentials of adlai. It was found that the crop is abundantly growing in the the country.

“BAR is promoting adlai as one of the important alternative food crops as part of the DA’s Food Staple Sufficiency Program. Part of the initiatives on adlai are adaptability trials nationwide to assess the performance of the different varieties of adlai which we were able to collect together with our R&D national and regional partners,” explained Dr. Nicomedes P. Eleazar, director of BAR.

He added that the results from this will be beneficial for the farmers who want to grow this crop in a commercial range as well as for the agriculture industry given our current challenge for rice sufficiency.”

R&D initiatives to promote adlai

Part of the on-going R&D initiatives of BAR on adlai is the documentation of production and indigenous practices of the crop in selected regions of the country. This initiative is conducted specifically to determine production and harvesting practices in adlai growing regions and use the data as technical basis in packaging location specific technologies. This will also provide relevant information for the recommendation of interventions and techniques to improve adlai production.

The project has six components: inventory of adlai varieties, agronomic characteristics of adlai varieties, uses of adlai and reasons for preference of adlai variety, ratoon yield, and production and harvesting practices.

Data were gathered through site visits, observations and interviews with the farmers’ associations and their members. The documentation team from BAR also used a structured questionnaire to determine adlai production and harvesting practices.

The documentation team—composed of technical staff from the Project Monitoring and Evaluation Division (PMED) and Applied Communication Division (ACD) and tapped experts— conducted series of group interview/discussions with key adlai farmer growers in identified growing areas of the country.

The five adlai growing areas include: Region 9 (Midsalip in Zamboanga del Sur); CAR (Sagada in Mt. Province, Kiangan in Ifugao, and Kapangan in Benguet); and Region 10 (Malaybalay in Bukidnon).

Result of the study showed that from the identified five adlai growing areas, it is only in Zamboanga del Sur where adlai was found to be growing robustly and is used as staple food and still cultivated mainly as food source. The use of adlai as staple food in other regions has diminished through time. Also, it was in Midsalip, Zamboanga del Sur wherein adlai germplasm is mostly rich.

Adlai seeds and varieties

Through the documentation that BAR conducted in adlai growing areas of the country, it was found that there are at least 11 local varieties of adlai. Specifically, these varieties are grown and widely cultivated in Regions 9, 10, and the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR).

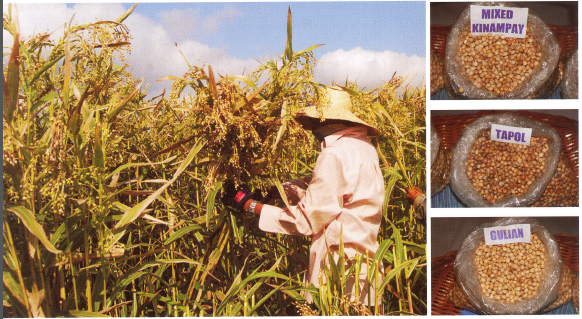

The 11 adlai varieties are: gulian, kinampay (ginampay), pulot (or tapol), linay, mataslai, bagelai, agle gestakyan, NOMIARC dwarf, jalayhay, and ag-gey. From these varieties, three are commonly grown and found in the country: gulian, kinampay (or ginampay), pulot (or tapol).

Adlai is widely grown in Region 9 particularly in Zamboanga del Sur mainly for food as alternative to rice and as ingredient for native wine (pangasi).

In Midsalip, report showed that from its 33 barangays, 19 are growing 1-3 adlai varieties including kinampay (brown), gulian (white), pulot or tapol (red or purple – glutinous) and linay (gold). Gulian variety is the most common cultivated variety and is refered to by the locals as “ordinary adlai”. Gulian and kinampay are the most popular varieties due to bigger size of grains, good eating quality, and higher yields.

According to the farmers in Midalip, they grow adlai with cash crops, including ginger, gabi, squash, forest trees and banana. Adlai has a profuse root system anchoring and preventing the big and sturdy tillers from lodging, hence farmers use it as hedgerow to prevent soil erosion.

In Dinas, farmers grow adlai (mataslai and bagelai) with upland rice. Mataslai variety is used for “pangasi” (native wine) and as substitute for rice while bagelai is commonly grown as monocrop in small patches of land.

In CAR region, adlai is cultivated for food, but majority for wine-making for special occasions, organic fertilizer (leaves, stems, dry panicles) and grains for feeds for livestock. In Sagada, farmers grow adlai (gestakyan variety) and reported that it was introduced to them by a farmer in Malibcong, Abra. For some time, they used it for food, and cooked it just like rice and found it a good alternate for rice. Other varieties of adlai are grown mainly for ornamental purpose, making necklace, rosary, bracelet, and table tray. She chopped the leaves and stems and used it as organic fertilizer.

In Kiangan, Ifugao, farmers grow adlai (agle variety) not for food. They use the leaves as organic fertilizer and its grains for making rosary and necklace. It grows abundantly in idle kaingin areas and along barangay roads with irrigation water.

In Kapangan and Benguet, the adlai variety grown is ag-gey (ag-gey in Kan-kanaey and ag-dey in Ibaloy). It is usually grown for food (roasted for coffee and sinaing na rice) and in small patches in their backyard and border plants for vegetables. Farmers also used the grains as feeds for cow.

Meanwhile, in Impasug-ong and Malaybaylay, Bukidnon, two adlai local varieties are grown: halayhay and NOMIARC dwarf (identified by DA-RFU 10/NOMIARC). Halayhay is grown by the Higaunan tribe and is used for wine, snacks (served with camote, gabi banana).

Documenting adlai production and indigenous practices

As the result of the documentation conducted by BAR, it was found that production practices are still very traditional, although low cost, environment-friendly, and sustainable.

For instance, in terms of cropping system, it was found that majority of the farmers grow adlai as mono crop. Others grow them with root crops (camote, gabi, cassava), fruit crops (banana) and cash crops (okra, squash, ginger), and forest trees.

Seed selection for planting material is found to be very effective in maintaining the purity of the seed quality. Farmers select seeds for planting materials by selecting long panicles, fuller grains from neck to head, good tiller stand and free from blackish spots or diseases. This careful seed selection is in contrast to what farmers in the lower elevation areas are doing where there is a very frequent varietal change due to varietal deterioration. In the lowlands, there is a perennial problem of seed source because of the absence of judicious seed selection.

They also use the leaves and other adlai parts of the plants as organic fertilizer. Other production practices include, clearing only the adlai root system areas to prevent soil erosion, and non-application of pesticide to preserve the population of beneficial insects.

Harvesting practices of adlai harvesting is also traditional shredding first the panicles with their hands after which they are milled and winnowed.

Farmers used “bayo” or mortar and pestle or a small wood in pounding adlai grain for food. Farmers’ roasts the grains, and pound/grind it continuously, winnow it using “bilao”. After series of winnowing, the adlai grits are now ready for cooking.

Yield performance of adlai varieties differs in different elevations. It thrives best in high with and cool temperature, coupled with good fertile soils, good cultural practices, no major pests observed, used of organic fertilizer which resulted to profuse rooting system and profuse tillering. Specifically in Midsalip, among the four varieties, kinampay produced the highest yield (3tons/ha) followed by gulian and pulot (2.8 tons/ha), and linay (2.7 tons/ha).

The documentation of adlai production and indigenous practices is critical in assessing the yield performance of different varieties of adlai growing in the area given the different elevations. This, according to BAR will be useful in the promotion and expansion of adlai in the future. ###

———

This article was based on the documentation report titled, “Documentation of Adlai Production Indigenous Practices in Selected Regions” conducted by BAR.

By: Rita T. Dela Cruz, BAR Digest October-December 2011 Issue (Vol. 13 No. 4)

ADLIA HAVE MANY USES

i truly believe that adlai is the right crop to battle poverty and hunger and all it needs is government committed intervention. what may we still look for a plant? this highly climate change resilient and nutritive crop is the answer, you don't waste any part of the plant